Stupid Gopher Tricks

GolangUK

21 August 2015

Andrew Gerrand

Andrew Gerrand

A video of this talk was recorded at GolangUK in London.

2This talk is about things you might not know about Go.

Some of this stuff you can add to your Go vocabulary.

Other things are probably best left for special occasions.

3Here's a familiar type declaration:

type Foo struct {

i int

s string

}The latter part of a type declaration is the type literal:

struct {

i int

s string

}

Other examples of type literals are int and []string,

which can also be declared as named types:

type Bar int type Qux []string

While we commonly use int and []string in variable declarations:

var i int var s []string

It is less common (but equally valid) to do the same with structs:

var t struct {

i int

s string

}An unnamed struct literal is often called an anonymous struct.

6A common use is providing data to templates:

// +build ignore

package main

import (

"log"

"os"

"strings"

"text/template"

)

func main() {

tmpl := template.Must(template.New("").Parse(strings.TrimSpace(`

Dear {{.Title}} {{.Lastname}},

Congratulations on reaching Level {{.Rank}}!

I'm sure your parents would say "Great job, {{.Firstname}}!"

Sincerely,

Rear Admiral Gopher

`)))

data := struct { Title string Firstname, Lastname string Rank int }{ "Dr", "Carl", "Sagan", 7, } if err := tmpl.Execute(os.Stdout, data); err != nil { log.Fatal(err) }

}

You could also use map[string]interface{},

but then you sacrifice performance and type safety.

The same technique can be used for encoding JSON objects:

// +build ignore

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

)

func main() {

b, err := json.Marshal(struct { ID int Name string }{42, "The answer"}) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } fmt.Printf("%s\n", b)

}

And also decoding:

// +build ignore

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

)

func main() {

var data struct { ID int Name string } err := json.Unmarshal([]byte(`{"ID": 42, "Name": "The answer"}`), &data) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } fmt.Println(data.ID, data.Name)

}

Structs can be nested to describe more complex JSON objects:

// +build ignore

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

)

func main() {

var data struct { ID int Person struct { Name string Job string } } const s = `{"ID":42,"Person":{"Name":"George Costanza","Job":"Architect"}}` err := json.Unmarshal([]byte(s), &data) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } fmt.Println(data.ID, data.Person.Name, data.Person.Job)

}

In repeated literals like slices and maps, Go lets you omit the inner type name:

type Foo struct { i int s string } var s = []Foo{ {6 * 9, "Question"}, {42, "Answer"}, } var m = map[int]Foo{ 7: {6 * 9, "Question"}, 3: {42, "Answer"}, }

Combined with anonymous structs, this convenience shortens the code dramatically:

var s = []struct { i int s string }{ struct { i int s string }{6 * 9, "Question"}, struct { i int s string }{42, "Answer"}, } var t = []struct { i int s string }{ {6 * 9, "Question"}, {42, "Answer"}, }

These properties enable a nice way to express test cases:

func TestIndex(t *testing.T) { var tests = []struct { s string sep string out int }{ {"", "", 0}, {"", "a", -1}, {"fo", "foo", -1}, {"foo", "foo", 0}, {"oofofoofooo", "f", 2}, // etc } for _, test := range tests { actual := strings.Index(test.s, test.sep) if actual != test.out { t.Errorf("Index(%q,%q) = %v; want %v", test.s, test.sep, actual, test.out) } } }

You can go a step further and put the composite literal in the range statement itself:

func TestIndex(t *testing.T) { for _, test := range []struct { s string sep string out int }{ {"", "", 0}, {"", "a", -1}, {"fo", "foo", -1}, {"foo", "foo", 0}, {"oofofoofooo", "f", 2}, // etc } { actual := strings.Index(test.s, test.sep) if actual != test.out { t.Errorf("Index(%q,%q) = %v; want %v", test.s, test.sep, actual, test.out) } } }

But this is harder to read.

13

A struct field that has no name is an embedded field.

The embedded type's methods (and fields, if it is a struct)

are accessible as if they are part of the embedding struct.

// +build ignore

package main

import "fmt"

type A struct { s string } func (a A) String() string { return fmt.Sprintf("A's String method called: %v", a.s) } type B struct { A } func main() { b := B{} b.s = "some value" fmt.Println(b) }

Of course, you can embed fields in an anonymous struct.

It's common to protect a global variable with a mutex variable:

var (

viewCount int64

viewCountMu sync.Mutex

)By embedding a mutex in an anonymous struct, we can group the related values:

var viewCount struct {

sync.Mutex

n int64

}

Users of viewCount access it like this:

viewCount.Lock() viewCount.n++ viewCount.Unlock()

And you can embed interfaces, too.

Here's a real example from Camlistore:

The function is expected to return a ReadSeekCloser,

but the programmer only had a string.

Anonymous struct (and its standard library friends) to the rescue!

return struct {

io.ReadSeeker

io.Closer

}{

io.NewSectionReader(strings.NewReader(s), 0, int64(len(s))),

ioutil.NopCloser(nil),

}

Interfaces can be anonymous, the most common being interface{}.

But the interface needn't be empty:

// +build ignore

package main

import (

"bytes"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

var s interface { String() string } = bytes.NewBufferString("I'm secretly a fmt.Stringer!") fmt.Println(s.String())

}

Useful for a sly type assertion (from src/os/exec/exec_test.go):

// Check that we can access methods of the underlying os.File.

if _, ok := stdin.(interface {

Fd() uintptr

}); !ok {

t.Error("can't access methods of underlying *os.File")

}

A "method value" is what you get when you evaluate a method as an expression.

The result is a function value.

Evaluating a method from a type yields a function:

// +build ignore

package main

import (

"bytes"

"os"

)

func main() {

var f func(*bytes.Buffer, string) (int, error) var buf bytes.Buffer f = (*bytes.Buffer).WriteString f(&buf, "y u no buf.WriteString?") buf.WriteTo(os.Stdout)

}

Evaluating a method from a value creates a closure that holds that value:

// +build ignore

package main

import (

"bytes"

"os"

)

func main() {

var f func(string) (int, error) var buf bytes.Buffer f = buf.WriteString f("Hey... ") f("this *is* cute.") buf.WriteTo(os.Stdout)

}

The sync.Once type is used to perform a task once with concurrency safety.

// Once is an object that will perform exactly one action.

type Once struct { /* Has unexported fields. */ }

func (o *Once) Do(f func())

This LazyPrimes type computes a slice of prime numbers the first time it is used:

type LazyPrimes struct { once sync.Once // Guards the primes slice. primes []int } func (p *LazyPrimes) init() { // Populate p.primes with prime numbers. } func (p *LazyPrimes) Primes() []int { p.once.Do(p.init) return p.primes }

You can use method values to implement multiple HTTP handlers with one type:

type Server struct { // Server state. } func (s *Server) index(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { /* Implementation. */ } func (s *Server) edit(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { /* Implementation. */ } func (s *Server) delete(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { /* Implementation. */ } func (s *Server) Register(mux *http.ServeMux) { mux.HandleFunc("/", s.index) mux.HandleFunc("/edit/", s.edit) mux.HandleFunc("/delete/", s.delete) }

In package os/exec, the Cmd type implements methods to set up

standard input, output, and error:

func (c *Cmd) stdin() (f *os.File, err error) func (c *Cmd) stdout() (f *os.File, err error) func (c *Cmd) stderr() (f *os.File, err error)

The caller handles each in the same way,

so it iterates over a slice of method values:

type F func(*Cmd) (*os.File, error)

for _, setupFd := range []F{(*Cmd).stdin, (*Cmd).stdout, (*Cmd).stderr} {

fd, err := setupFd(c)

if err != nil {

c.closeDescriptors(c.closeAfterStart)

c.closeDescriptors(c.closeAfterWait)

return err

}

c.childFiles = append(c.childFiles, fd)

}

The Go spec defines a set of types as "comparable";

they may be compared with == and !=.

Bools, ints, floats, complex numbers, strings, pointers,

channels, structs, and interfaces are comparable.

// +build ignore

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var a, b int = 42, 42 fmt.Println(a == b) var i, j interface{} = a, b fmt.Println(i == j) var s, t struct{ i interface{} } s.i, t.i = a, b fmt.Println(s == t)

}

A struct is comparable only if its fields are comparable:

// +build ignore

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var q, r struct{ s []string } fmt.Println(q == r)

}

Any comparable type may be used as a map key.

a := map[int]bool{} a[42] = true type T struct { i int s string } b := map[*T]bool{} b[&T{}] = true c := map[T]bool{} c[T{37, "hello!"}] = true d := map[interface{}]bool{} d[42] = true d[&T{}] = true d[T{123, "four five six"}] = true d[ioutil.Discard] = true

An example from the Go continuous build infrastructure:

type builderRev struct {

builder, rev string

}

var br = builderRev{"linux-amd64", "0cd299"}

We track in-flight builds in a map.

The pre-Go 1 way was to flatten the data to a string first:

inflight := map[string]bool{}

inflight[br.builder + "-" + br.rev] = trueBut with struct keys, you can avoid the allocation and have cleaner code:

inflight := map[builderRev]bool{}

inflight[br] = true

An example of interface map keys from Docker's broadcastwriter package:

type BroadcastWriter struct { sync.Mutex writers map[io.WriteCloser]struct{} } func (w *BroadcastWriter) AddWriter(writer io.WriteCloser) { w.Lock() w.writers[writer] = struct{}{} w.Unlock() } func (w *BroadcastWriter) Write(p []byte) (n int, err error) { w.Lock() for sw := range w.writers { if n, err := sw.Write(p); err != nil || n != len(p) { delete(w.writers, sw) } } w.Unlock() return len(p), nil }

A (very) contrived example: (Don't do this! Ever!)

// +build ignore

package main

import "fmt"

type cons struct { car string cdr interface{} } func (c cons) String() string { if c.cdr == nil || c.cdr == (cons{}) { return c.car } return fmt.Sprintf("%v %v", c.car, c.cdr) } func main() { m := map[cons]string{} c := cons{} for _, s := range []string{"life?", "with my", "I doing", "What am"} { c = cons{s, c} } m[c] = "No idea." fmt.Println(c, m[c]) }

For a simple counter, you can use the sync/atomic package's

functions to make atomic updates without the lock.

func AddInt64(addr *int64, delta int64) (new int64) func CompareAndSwapInt64(addr *int64, old, new int64) (swapped bool) func LoadInt64(addr *int64) (val int64) func StoreInt64(addr *int64, val int64) func SwapInt64(addr *int64, new int64) (old int64)

First, define the global variable (appropriately documented!):

// viewCount must be updated atomically. var viewCount int64

Then increment it with AddInt64:

count := atomic.AddInt64(&viewCount, 1)

The set are available for Int32, Uint32, Int64, Uint64, Pointer, and Uintptr.

Another option for sharing state is atomic.Value.

For instance, to share configuration between many goroutines:

type Config struct {

Timeout time.Duration

}

var config atomic.Value

To set or update, use the Store method:

config.Store(&Config{Timeout: 2*time.Second})

To read, each goroutine calls the Load method:

cfg := config.Load().(*Config)

Note that storing different types in the same Value will cause a panic.

The atomic.Value primitive is the size of a single interface value:

package atomic

type Value struct {

v interface{}

}

An interface value is represented by the runtime as two pointers:

one for the type, and one for the value.

// ifaceWords is interface{} internal representation.

type ifaceWords struct {

typ unsafe.Pointer

data unsafe.Pointer

}

To load and store an interface value atomically, it operates on the parts of the interface value with atomic.LoadPointer and atomic.StorePointer.

The Store method first validates the input:

func (v *Value) Store(x interface{}) {

if x == nil {

panic("sync/atomic: store of nil value into Value")

}

Then uses unsafe to cast the current and new interface{} values to ifaceWords:

// ...

vp := (*ifaceWords)(unsafe.Pointer(v))

xp := (*ifaceWords)(unsafe.Pointer(&x))(This allows us to get at the internals of those interface values.)

31Spin while loading the type field:

// ...

for {

typ := LoadPointer(&vp.typ)

If it's nil the this is the first time the value has been stored.

Put a sentinel value (max uintptr) in the type field to "lock" it while we work with it:

// ...

if typ == nil {

if !CompareAndSwapPointer(&vp.typ, nil, unsafe.Pointer(^uintptr(0))) {

continue // Someone beat us to it. Wait.

}Store the data field, then the type field, and we're done!

// ...

StorePointer(&vp.data, xp.data)

StorePointer(&vp.typ, xp.typ)

return

}If this isn't the first store, check whether a store is already happening:

// ...

if uintptr(typ) == ^uintptr(0) {

continue // First store in progress. Wait.

}Sanity check whether the type changed:

// ...

if typ != xp.typ {

panic("sync/atomic: store of inconsistently typed value into Value")

}If the type field is what we expect, go ahead and atomically store the value:

// ...

StorePointer(&vp.data, xp.data)

return

}

}

The Load method first loads the interface's type field:

func (v *Value) Load() (x interface{}) {

vp := (*ifaceWords)(unsafe.Pointer(v))

typ := LoadPointer(&vp.typ)Then, check whether a store has happened, or is happening:

// ...

if typ == nil || uintptr(typ) == ^uintptr(0) {

return nil

}Otherwise, load the data field and return both type and data as a new interface value:

// ...

data := LoadPointer(&vp.data)

xp := (*ifaceWords)(unsafe.Pointer(&x))

xp.typ = typ

xp.data = data

return

}Usually you don't want or need the stuff in this package.

Try channels or the sync package first.

You almost certainly shouldn't write code like the atomic.Value implementation.

(And I didn't show all of it; the real code has hooks into the runtime.)

Sometimes you need to test the behavior of a process, not just a function.

func Crasher() { fmt.Println("Going down in flames!") os.Exit(1) }

To test this code, we invoke the test binary itself as a subprocess:

func TestCrasher(t *testing.T) { if os.Getenv("BE_CRASHER") == "1" { Crasher() return } cmd := exec.Command(os.Args[0], "-test.run=TestCrasher") cmd.Env = append(os.Environ(), "BE_CRASHER=1") err := cmd.Run() if e, ok := err.(*exec.ExitError); ok && !e.Success() { return } t.Fatalf("process ran with err %q, want exit status 1", err) }

Go's CPU and memory profilers report data for an entire process.

To profile just one side of a concurrent operation, you can use a sub-process.

This benchmark from the net/http package spawns a child process to make

requests to a server running in the main process.

func BenchmarkServer(b *testing.B) {

b.ReportAllocs()

// Child process mode;

if url := os.Getenv("TEST_BENCH_SERVER_URL"); url != "" {

n, err := strconv.Atoi(os.Getenv("TEST_BENCH_CLIENT_N"))

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

res, err := Get(url)

// ...

}

os.Exit(0)

return

}

// ...// ...

res := []byte("Hello world.\n")

ts := httptest.NewServer(HandlerFunc(func(rw ResponseWriter, r *Request) {

rw.Header().Set("Content-Type", "text/html; charset=utf-8")

rw.Write(res)

}))

defer ts.Close()

cmd := exec.Command(os.Args[0], "-test.run=XXXX", "-test.bench=BenchmarkServer$")

cmd.Env = append([]string{

fmt.Sprintf("TEST_BENCH_CLIENT_N=%d", b.N),

fmt.Sprintf("TEST_BENCH_SERVER_URL=%s", ts.URL),

}, os.Environ()...)

if out, err := cmd.CombinedOutput(); err != nil {

b.Errorf("Test failure: %v, with output: %s", err, out)

}

}To run:

$ go test -run=XX -bench=BenchmarkServer -benchtime=15s -cpuprofile=http.prof $ go tool pprof http.test http.prof

$ go help list usage: go list [-e] [-f format] [-json] [build flags] [packages] List lists the packages named by the import paths, one per line.

Show the packages under a path:

$ go list golang.org/x/oauth2/... golang.org/x/oauth2 ... golang.org/x/oauth2/vk

Show the standard library:

$ go list std archive/tar ... unsafe

Show all packages:

$ go list all

The -json flag tells you everything the go tool knows about a package:

$ go list -json bytes

{

"Dir": "/Users/adg/go/src/bytes",

"ImportPath": "bytes",

"Name": "bytes",

"Doc": "Package bytes implements functions for the manipulation of byte slices.",

"Target": "/Users/adg/go/pkg/darwin_amd64/bytes.a",

"Goroot": true,

"Standard": true,

"Stale": true,

"Root": "/Users/adg/go",

"GoFiles": [

"buffer.go",

"bytes.go",

"bytes_decl.go",

"reader.go"

],

...

}It's easy to write programs that consume this data.

43

The go tool's documented Package struct describes all the possible fields:

type Package struct {

Dir string // directory containing package sources

ImportPath string // import path of package in dir

ImportComment string // path in import comment on package statement

Name string // package name

Doc string // package documentation string

Target string // install path

Shlib string // the shared library that contains this package (only set when -linkshared)

Goroot bool // is this package in the Go root?

Standard bool // is this package part of the standard Go library?

Stale bool // would 'go install' do anything for this package?

Root string // Go root or Go path dir containing this package

// (more fields on next slide)

}type Package struct {

// (more fields on previous slide)

// Source files

GoFiles []string // .go source files (excluding CgoFiles, TestGoFiles, XTestGoFiles)

CgoFiles []string // .go sources files that import "C"

IgnoredGoFiles []string // .go sources ignored due to build constraints

CFiles []string // .c source files

CXXFiles []string // .cc, .cxx and .cpp source files

MFiles []string // .m source files

HFiles []string // .h, .hh, .hpp and .hxx source files

SFiles []string // .s source files

SwigFiles []string // .swig files

SwigCXXFiles []string // .swigcxx files

SysoFiles []string // .syso object files to add to archive

// (more fields on next slide)

}type Package struct {

// (more fields on previous slide)

// Cgo directives

CgoCFLAGS []string // cgo: flags for C compiler

CgoCPPFLAGS []string // cgo: flags for C preprocessor

CgoCXXFLAGS []string // cgo: flags for C++ compiler

CgoLDFLAGS []string // cgo: flags for linker

CgoPkgConfig []string // cgo: pkg-config names

// Dependency information

Imports []string // import paths used by this package

Deps []string // all (recursively) imported dependencies

// Error information

Incomplete bool // this package or a dependency has an error

Error *PackageError // error loading package

DepsErrors []*PackageError // errors loading dependencies

TestGoFiles []string // _test.go files in package

TestImports []string // imports from TestGoFiles

XTestGoFiles []string // _test.go files outside package

XTestImports []string // imports from XTestGoFiles

}That's a ton of information, so what can we do with it?

The -f flag lets you use Go's text/template package to format the ouput.

Show package doc strings:

$ go list -f '{{.Doc}}' golang.org/x/oauth2/...

Package oauth2 provides support for making OAuth2 authorized and authenticated HTTP requests.

Package jwt implements the OAuth 2.0 JSON Web Token flow, commonly known as "two-legged OAuth 2.0".

...Show the Go files in a package:

$ go list -f '{{.GoFiles}}' bytes

[buffer.go bytes.go bytes_decl.go reader.go]

Make the output cleaner with a join:

$ go list -f '{{join .GoFiles " "}}' bytes

buffer.go bytes.go bytes_decl.go reader.goWith template logic we can test packages for certain conditions.

Find standard libraries that lack documentation:

$ go list -f '{{if not .Doc}}{{.ImportPath}}{{end}}' std

internal/format

internal/traceFind packages that depend (directly or indirectly) on a given package:

$ go list -f '{{range .Deps}}{{if eq . "golang.org/x/oauth2"}}{{$.ImportPath}}{{end}}{{end}}' all

golang.org/x/build/auth

golang.org/x/build/buildlet

golang.org/x/build/cmd/buildlet

...

Find packages that are broken somehow (note -e):

$ go list -e -f '{{with .Error}}{{.}}{{end}}' all

package github.com/golang/oauth2: code in directory /Users/adg/src/github.com/golang/oauth2

expects import "golang.org/x/oauth2"

...Things get interesting once we start using the shell.

For instance, we can use go list output as input to the go tool.

Test all packages except vendored packages:

$ go test $(go list ./... | grep -v '/vendor/')

Test the dependencies of a specific package:

$ go test $(go list -f '{{join .Deps " "}}' golang.org/x/oauth2)The same, but don't test the standard library:

$ go test $(

go list -f '{{if (not .Goroot)}}{{.ImportPath}}{{end}}' $(

go list -f '{{join .Deps " "}}' golang.org/x/oauth2

)

)for pkg in $(go list golang.org/x/oauth2/...); do

wc -l $(go list -f '{{range .GoFiles}}{{$.Dir}}/{{.}} {{end}}' $pkg) | \

tail -1 | awk '{ print $1 " '$pkg'" }'

done | sort -nrThe output:

617 golang.org/x/oauth2/google 600 golang.org/x/oauth2 357 golang.org/x/oauth2/internal 160 golang.org/x/oauth2/jws 147 golang.org/x/oauth2/jwt 112 golang.org/x/oauth2/clientcredentials 22 golang.org/x/oauth2/paypal 16 golang.org/x/oauth2/vk 16 golang.org/x/oauth2/odnoklassniki 16 golang.org/x/oauth2/linkedin 16 golang.org/x/oauth2/github 16 golang.org/x/oauth2/facebook

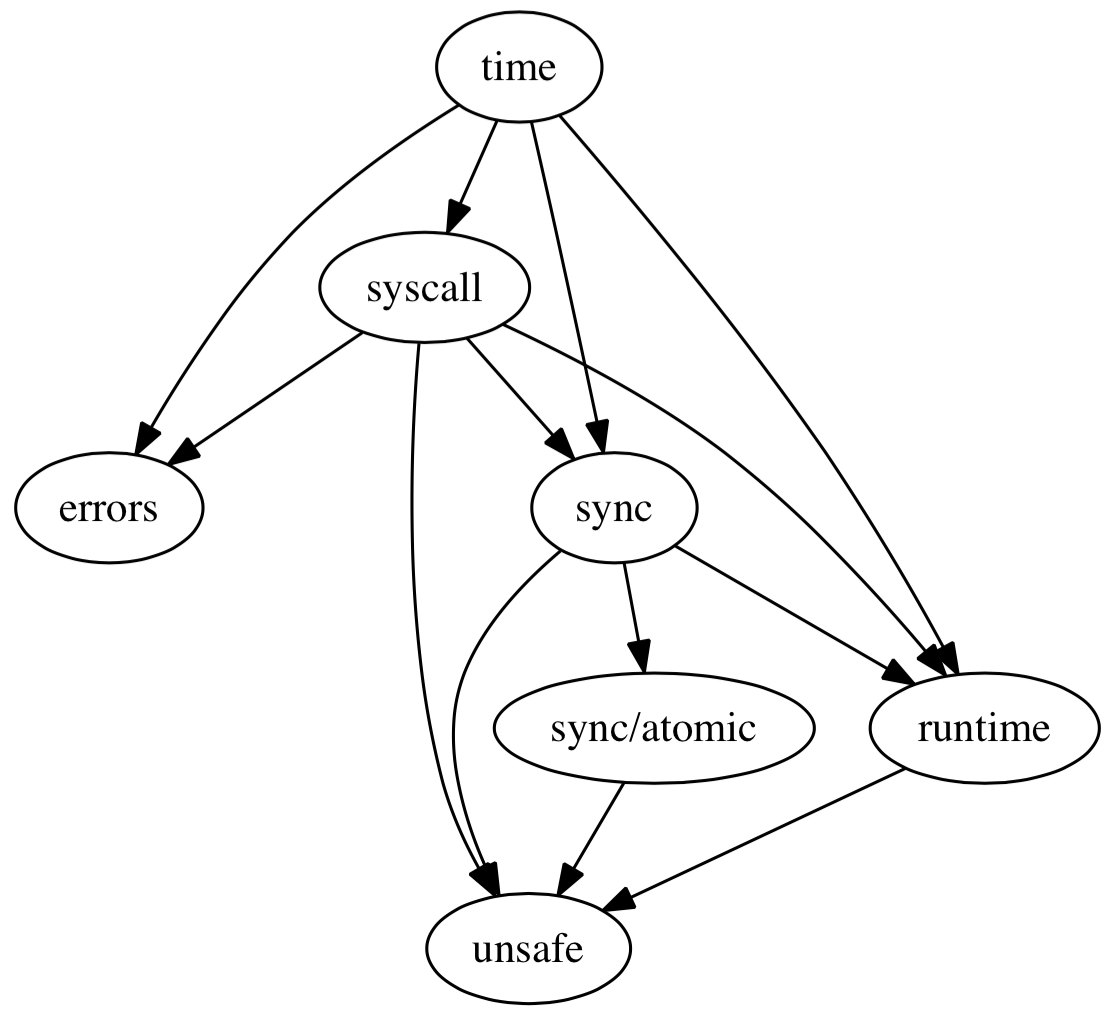

( echo "digraph G {"

go list -f '{{range .Imports}}{{printf "\t%q -> %q;\n" $.ImportPath .}}{{end}}' \

$(go list -f '{{join .Deps " "}}' time) time

echo "}"

) | dot -Tsvg -o time-deps.svg

There are many more fun corners of Go.

Can you find them all? :-)

Read the docs, explore, and have fun!

52Andrew Gerrand