The Go Blog

HTTP/2 Server Push

Introduction

HTTP/2 is designed to address many of the failings of HTTP/1.x. Modern web pages use many resources: HTML, stylesheets, scripts, images, and so on. In HTTP/1.x, each of these resources must be requested explicitly. This can be a slow process. The browser starts by fetching the HTML, then learns of more resources incrementally as it parses and evaluates the page. Since the server must wait for the browser to make each request, the network is often idle and underutilized.

To improve latency, HTTP/2 introduced server push, which allows the server to push resources to the browser before they are explicitly requested. A server often knows many of the additional resources a page will need and can start pushing those resources as it responds to the initial request. This allows the server to fully utilize an otherwise idle network and improve page load times.

At the protocol level, HTTP/2 server push is driven by PUSH_PROMISE

frames. A PUSH_PROMISE describes a request that the server predicts the

browser will make in the near future. As soon as the browser receives

a PUSH_PROMISE, it knows that the server will deliver the resource.

If the browser later discovers that it needs this resource, it will

wait for the push to complete rather than sending a new request.

This reduces the time the browser spends waiting on the network.

Server Push in net/http

Go 1.8 introduced support for pushing responses from an http.Server.

This feature is available if the running server is an HTTP/2 server

and the incoming connection uses HTTP/2. In any HTTP handler,

you can assert if the http.ResponseWriter supports server push by checking

if it implements the new http.Pusher interface.

For example, if the server knows that app.js will be required to

render the page, the handler can initiate a push if http.Pusher

is available:

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if pusher, ok := w.(http.Pusher); ok {

// Push is supported.

if err := pusher.Push("/app.js", nil); err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed to push: %v", err)

}

}

// ...

})

The Push call creates a synthetic request for /app.js,

synthesizes that request into a PUSH_PROMISE frame, then forwards

the synthetic request to the server’s request handler, which will

generate the pushed response. The second argument to Push specifies

additional headers to include in the PUSH_PROMISE. For example,

if the response to /app.js varies on Accept-Encoding,

then the PUSH_PROMISE should include an Accept-Encoding value:

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if pusher, ok := w.(http.Pusher); ok {

// Push is supported.

options := &http.PushOptions{

Header: http.Header{

"Accept-Encoding": r.Header["Accept-Encoding"],

},

}

if err := pusher.Push("/app.js", options); err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed to push: %v", err)

}

}

// ...

})

A fully working example is available here.

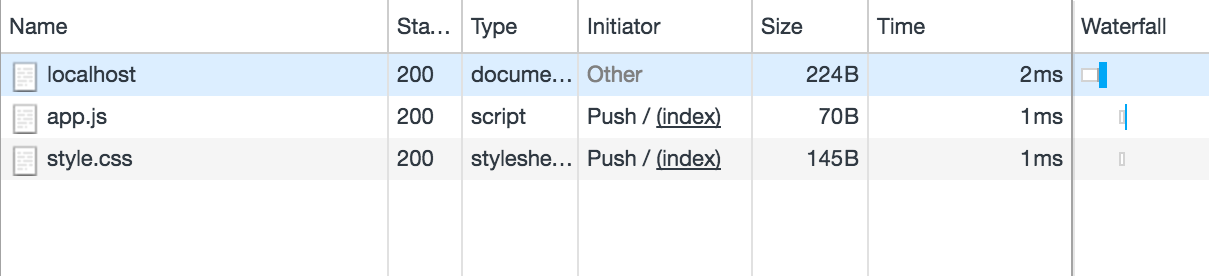

If you run the server and load https://localhost:8080,

your browser’s developer tools should show that app.js and

style.css were pushed by the server.

Start Your Pushes Before You Respond

It’s a good idea to call the Push method before sending any bytes of the response. Otherwise it is possible to accidentally generate duplicate responses. For example, suppose you write part of an HTML response:

<html>

<head>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="a.css">...

Then you call Push(“a.css”, nil). The browser may parse this fragment

of HTML before it receives your PUSH_PROMISE, in which case the browser

will send a request for a.css in addition to receiving your

PUSH_PROMISE. Now the server will generate two responses for a.css.

Calling Push before writing the response avoids this possibility entirely.

When To Use Server Push

Consider using server push any time your network link is idle. Just finished sending the HTML for your web app? Don’t waste time waiting, start pushing the resources your client will need. Are you inlining resources into your HTML file to reduce latency? Instead of inlining, try pushing. Redirects are another good time to use push because there is almost always a wasted round trip while the client follows the redirect. There are many possible scenarios for using push – we are only getting started.

We would be remiss if we did not mention a few caveats. First, you can only push resources your server is authoritative for – this means you cannot push resources that are hosted on third-party servers or CDNs. Second, don’t push resources unless you are confident they are actually needed by the client, otherwise your push wastes bandwidth. A corollary is to avoid pushing resources when it’s likely that the client already has those resources cached. Third, the naive approach of pushing all resources on your page often makes performance worse. When in doubt, measure.

The following links make for good supplemental reading:

- HTTP/2 Push: The Details

- Innovating with HTTP/2 Server Push

- Cache-Aware Server Push in H2O

- The PRPL Pattern

- Rules of Thumb for HTTP/2 Push

- Server Push in the HTTP/2 spec

Conclusion

With Go 1.8, the standard library provides out-of-the-box support for HTTP/2 Server Push, giving you more flexibility to optimize your web applications.

Go to our HTTP/2 Server Push demo page to see it in action.

Next article: Introducing the Developer Experience Working Group

Previous article: Go 2016 Survey Results

Blog Index