Go for C++ developers

Francesc Campoy

Developer, Advocate, and Gopher at Google

Francesc Campoy

Developer, Advocate, and Gopher at Google

Agenda:

2011 Joined Google as a Software Engineer

2012 Joined the Go team as a Developer Programs Engineer

2014 to today Developer Advocate for the Google Cloud Platform

3Go is

Go was created for:

Google:

Others:

int, uint, int8, uint8, ... bool, string float32, float64 complex64, complex128

struct {

Name string

Age int

}[]int, [3]string, []struct{ Name string }map[string]int

*int, *Person

func(int, int) int

chan bool

interface {

Start()

Stop()

}type [name] [specification]

Person is a struct type.

type Person struct {

name string

age int

}

Celsius is a float64 type.

type Celsius float64

func [name] ([params]) [return value] func [name] ([params]) ([return values])

A sum function:

func sum(a int, b int) int {

return a + b

}A function with multiple return values:

func divMod(a, b int) (int, int) {

return a / b, a % b

}Made clearer by naming the return values:

func divMod(den, div int) (quo, rem int) {

return den / div, den % div

}func ([receiver]) [name] ([params]) ([return values])

A method on a struct:

func (p Person) IsMinor() bool {

return p.age < 18

}

But also a method on a float64:

func (c Celsius) Freezing() bool {

return c <= 0

}Constraint: Methods can be defined only on types declared in the same package.

// This won't compile

func (s string) Length() int { return len(s) }Normal declaration:

var text string = "hello"

You can omit types:

var text = "hello"

And inside of functions:

text := "hello"

Other types

a := 0 // int

b := true // boolean

f := 1.0 // float64

p := Person{"Francesc", "Campoy"} // PersonGiven types:

type Celsius float64 type Fahrenheit float64

And the variables:

var freezing Fahrenheit = 32 var boiling Celsius = 100

This code won't compile:

sauna := (freezing + boiling) / 2

There's no implicit numeric conversion in Go.

16Go has pointers:

var p *int p = new(int)

But no pointer arithmetics:

var p *int = &a[0] var q = p+2 // invalid

There's new but there's no delete.

Memory is garbage collected after it's no longer accessible.

18The compiler decides where to allocate based on escape analysis.

Using new doesn't imply using the heap:

stack.go:

func get() int {

n := new(int)

return *n

}

And not all values in the heap are created with new:

heap.go:

func get() *int {

n := 4

return &n

}You can not decide where a value is allocated.

But you can see what kind of allocation is used:

$ go tool 6g -m stack.go stack.go:3: can inline get stack.go:4: get new(int) does not escape

Compare to:

$ go tool 6g -m heap.go heap.go:3: can inline get heap.go:4: moved to heap: n heap.go:5: &n escapes to heap

Resource Acquisition Is Initialization

Provides:

An example:

void write_to_file (const std::string & message) {

// mutex to protect file access

static std::mutex mutex;

// lock mutex before accessing file

// at the end of the scope unlock mutex

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mutex);

// mutual exclusion access section

...

}

The defer statement:

var m sync.Mutex

func writeToFile(msg string) error {

m.Lock()

defer m.Unlock()

// mutual exclusion access section

}Go is a garbage collected language

But it's easy to limit heap allocations

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"unsafe"

)

type Date struct { Day int Month int Year int } func main() { fmt.Printf("size of %T: %v\n", 0, unsafe.Sizeof(0)) fmt.Printf("size of %T: %v\n", Date{}, unsafe.Sizeof(Date{})) fmt.Printf("size of %T: %v\n", [100]Date{}, unsafe.Sizeof([100]Date{})) }

Trusted in production.

Brad Fitzpatrick's talk on migrating dl.google.com from C++ to Go:

Current state and road plan:

24Example:

type Engine struct{}

func (e Engine) Start() { ... }

func (e Engine) Stop() { ... }

We want Car to be able to Start and Stop too.

More detail in my talk Go for Javaneros

26Composition + Proxy of selectors

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import "fmt"

type Engine struct{} func (e Engine) Start() { fmt.Println("Engine started") } func (e Engine) Stop() { fmt.Println("Engine stopped") } type Car struct { Engine // Notice the lack of name } func main() { var c Car c.Start() c.Stop() }

What if two embedded fields have the same type?

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import "fmt"

type Engine struct{} func (e Engine) Start() { fmt.Println("Engine started") } func (e Engine) Stop() { fmt.Println("Engine stopped") } type Radio struct{} func (r Radio) Start() { fmt.Println("Radio started") } func (r Radio) Stop() { fmt.Println("Radio stopped") } type Car struct { Engine Radio } func main() { var c Car c.Radio.Start() c.Engine.Start() }

It looks like inheritance but it is not inheritance.

It is composition.

Used to share implementations between different types.

What if want to share behavior instead?

29An interface is a set of methods.

In Java (C++ doesn't have interfaces)

interface Switch {

void open();

void close();

}In Go:

type OpenCloser interface {

Open()

Close()

}Java interfaces are satisfied explicitly.

C++ abstract classes need to be extended explicitly

Go interfaces are satisfied implicitly.

If a type defines all the methods of an interface, the type satisfies that interface.

Benefits:

Better than duck typing. Verified at compile time.

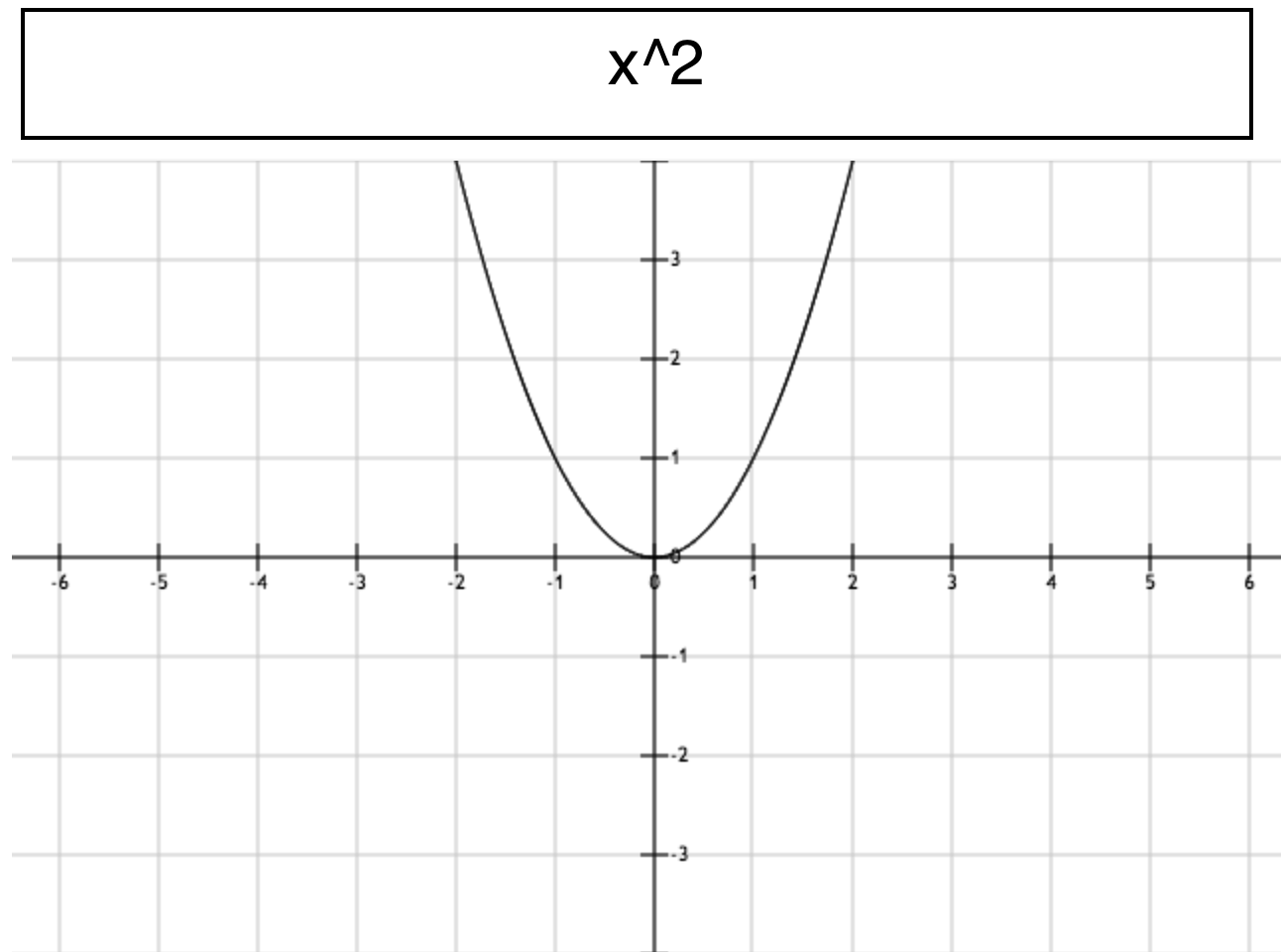

Package parse provides a parser of strings into functions.

func Parse(text string) (*Func, error) { ... }

Func is a struct type, with an Eval method.

type Func struct { ... }

func (p *Func) Eval(x float64) float64 { ... }Package draw generates images given a function.

func Draw(f *parser.Func) image.Image {

for x := start; x < end; x += inc {

y := f.Eval(x)

...

}

}

draw depends on parser, which makes testing hard.

Let's use an interface instead

type Evaluable interface {

Eval(float64) float64

}

func Draw(f Evaluable) image.Image image.Image {

for x := start; x < end; x += inc {

y := f.Eval(x)

...

}

}Embedding an interface:

Given:

type Person struct {

First string

Last string

Age int

}

Employee exposes the Age of Person

type Employee struct {

Person

}

e := Employee{Person{"John", "Doe", 49}}But we could hide it by choosing an interface:

type Employee struct {

Namer

}

type Namer interface {

Name() string

}

And we need to make Person satisfy Namer

func (e Person) Name() string { return e.First + e.Last }And the rest of the code still works:

e := Employee{Person{"John", "Doe", 49}}Given this function:

func CheckPassword(c net.Conn) error { // read a password from the connection buf := make([]byte, 256) n, err := c.Read(buf) if err != nil { return fmt.Errorf("read: %v", err) } // check it's correct got := string(buf[:n]) if got != "password" { return fmt.Errorf("wrong password") } return nil }

How would you test it?

42

net.Conn is an interface defined in the net package of the standard library.

type Conn interface {

Read(b []byte) (n int, err error)

Write(b []byte) (n int, err error)

Close() error

LocalAddr() Addr

RemoteAddr() Addr

SetDeadline(t time.Time) error

SetReadDeadline(t time.Time) error

SetWriteDeadline(t time.Time) error

}

We need a fake net.Conn!

We could define a new type that satisfies net.Conn

type fakeConn struct {}

func (c fakeConn) Read(b []byte) (n int, err error) {...}

func (c fakeConn) Write(b []byte) (n int, err error) {...}

func (c fakeConn) Close() error {...}

...But, is there a better way?

44type fakeConn struct { net.Conn r io.Reader } func (c fakeConn) Read(b []byte) (int, error) { return c.r.Read(b) }

And our test can look like:

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"io"

"log"

"net"

"strings"

)

func CheckPassword(c net.Conn) error {

// read a password from the connection

buf := make([]byte, 256)

n, err := c.Read(buf)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("read: %v", err)

}

// check it's correct

got := string(buf[:n])

if got != "password" {

return fmt.Errorf("wrong password")

}

return nil

}

type fakeConn struct {

net.Conn

r io.Reader

}

func (c fakeConn) Read(b []byte) (int, error) {

return c.r.Read(b)

}

// end_fake OMIT

func main() { c := fakeConn{ r: strings.NewReader("foo"), } err := CheckPassword(c) if err == nil { log.Println("expected error using wrong password") } else { log.Println("OK") } }

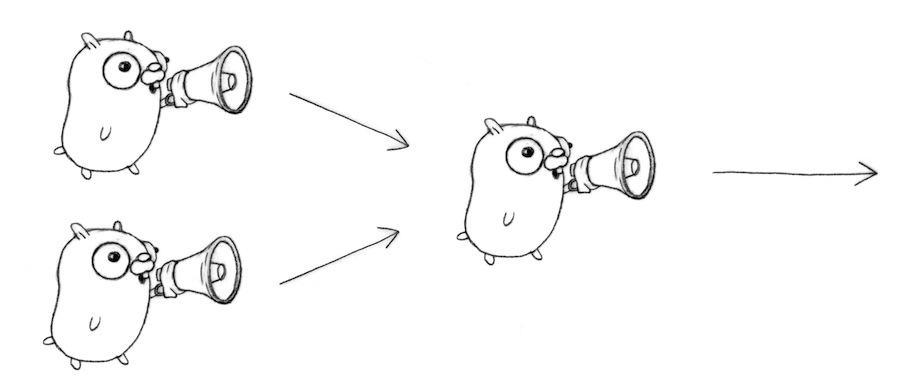

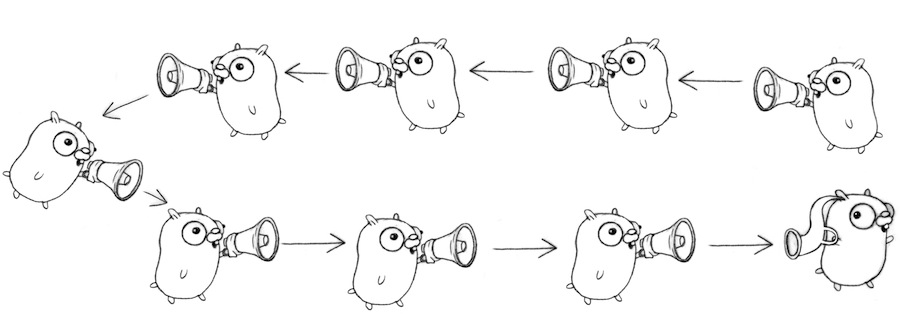

It is part of the language, not a library.

Based on three concepts:

func sleepAndTalk(t time.Duration, msg string) { time.Sleep(t) fmt.Printf("%v ", msg) }

We want a message per second.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func sleepAndTalk(t time.Duration, msg string) {

time.Sleep(t)

fmt.Printf("%v ", msg)

}

func main() { sleepAndTalk(0*time.Second, "Hello") sleepAndTalk(1*time.Second, "Gophers!") sleepAndTalk(2*time.Second, "What's") sleepAndTalk(3*time.Second, "up?") }

What if we started all the sleepAndTalk concurrently?

Just add go!

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func sleepAndTalk(t time.Duration, msg string) {

time.Sleep(t)

fmt.Printf("%v ", msg)

}

func main() { go sleepAndTalk(0*time.Second, "Hello") go sleepAndTalk(1*time.Second, "Gophers!") go sleepAndTalk(2*time.Second, "What's") go sleepAndTalk(3*time.Second, "up?") }

That was fast ...

When the main goroutine ends, the program ends.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func sleepAndTalk(t time.Duration, msg string) {

time.Sleep(t)

fmt.Printf("%v ", msg)

}

func main() { go sleepAndTalk(0*time.Second, "Hello") go sleepAndTalk(1*time.Second, "Gophers!") go sleepAndTalk(2*time.Second, "What's") go sleepAndTalk(3*time.Second, "up?") time.Sleep(4 * time.Second) }

But synchronizing with Sleep is a bad idea.

sleepAndTalk sends the string into the channel instead of printing it.

func sleepAndTalk(secs time.Duration, msg string, c chan string) { time.Sleep(secs * time.Second) c <- msg }

We create the channel and pass it to sleepAndTalk, then wait for the values to be sent.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func sleepAndTalk(secs time.Duration, msg string, c chan string) {

time.Sleep(secs * time.Second)

c <- msg

}

func main() { c := make(chan string) go sleepAndTalk(0, "Hello", c) go sleepAndTalk(1, "Gophers!", c) go sleepAndTalk(2, "What's", c) go sleepAndTalk(3, "up?", c) for i := 0; i < 4; i++ { fmt.Printf("%v ", <-c) } }

A production ready web server.

package main import ( "fmt" "log" "net/http" ) func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintln(w, "hello") } func main() { http.HandleFunc("/", handler) err := http.ListenAndServe("localhost:1234", nil) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } }

Why is this wrong?

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

)

var nextID int func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, q *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintf(w, "<h1>You got %v<h1>", nextID) nextID++ } func main() { http.HandleFunc("/", handler) log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe("localhost:8080", nil)) }

We receive the next id from a channel.

var nextID = make(chan int) func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, q *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintf(w, "<h1>You got %v<h1>", <-nextID) }

We need to send ids into the channel.

func counter() { for i := 0; ; i++ { nextID <- i } }

And we need to do both at the same time.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

)

var nextID = make(chan int)

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, q *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "<h1>You got %v<h1>", <-nextID)

}

func counter() {

for i := 0; ; i++ {

nextID <- i

}

}

func main() { http.HandleFunc("/", handler) go counter() log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe("localhost:8080", nil)) }

select allows us to choose among multiple channel operations.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

var battle = make(chan string) func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, q *http.Request) { select { case battle <- q.FormValue("usr"): fmt.Fprintf(w, "You won!") case won := <-battle: fmt.Fprintf(w, "You lost, %v is better than you", won) } }

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/fight", handler)

http.ListenAndServe("localhost:8080", nil)

}

Go - localhost:8080/fight?usr=go

C++ - localhost:8080/fight?usr=cpp

Ok, I'm just bragging here

57// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func f(left, right chan int) { left <- 1 + <-right } func main() { start := time.Now() const n = 1000 leftmost := make(chan int) right := leftmost left := leftmost for i := 0; i < n; i++ { right = make(chan int) go f(left, right) left = right } go func(c chan int) { c <- 0 }(right) fmt.Println(<-leftmost, time.Since(start)) }

And there's lots to learn!

Learn Go on your browser with go.dev/tour

Find more about Go on go.dev

Join the community at golang-nuts

Link to the slides /talks/2015/go4cpp.slide

61